The text on the site is translated into English, errors are possible. Sorry...

From Flint to Steel parts 2

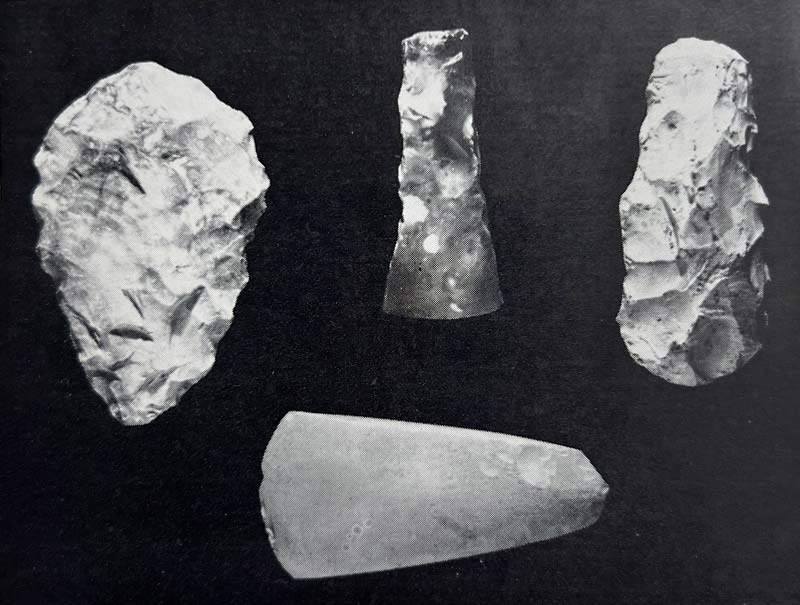

Some 8,000 or 10,000 years before the birth of Christ there was another significant development, for there appeared very large numbers of microliths which must have required a great deal of skill and patience in manufacture. These were extremely small shaped pieces of flint; they were not simply the odd pieces left over when shaping another larger tool but were carefully made in their own right. In size they were often less than half an inch long and were made in a variety of shapes; triangular, square and other more complex shapes have all been found. By 6,000 years B.C. man’s skill in working flint and bone had increased enormously. Microliths were still being made, as were the blade tools; but now arrow heads, stone axes, and club heads were being produced which were remarkable for the beauty of their finish. Gone were the rough serrated faces of the earlier examples; man now produced a wide range of smooth, delicately finished and beautifully modelled stone tools and weapons.

Primitive man soon learnt from bitter experience the value of a sharp weapon, and although there is no evidence to suggest that the first men (such as Peking Man) used flint for the heads of spears or axes, it seems not at all unreasonable to assume that they would have made full use of wooden spears. It is more than likely that the points of these spears would be hardened by charring in a fire, for there is clear evidence that Peking man knew and used fire. There can be no doubt that such wooden spears were remarkably effective; one made of yew wood, nearly eight feet long, was found between the ribs of an elephant skeleton excavated in Lower Saxony in Germany.

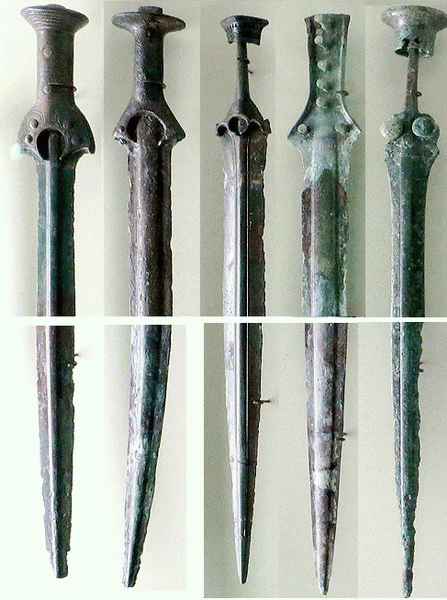

Fig. 3: Flint implements: left, North American Indian lance head (?) from Ohio, length 4 inches; centre top, arrowhead from Barking, Essex, length 2 inches; centre middle, Danish Neolithic scraper or knife, length 4 inches; centre bottom, Danish Neolithic lance head or knife, length inches; right, North American Indian lance head, length inches. {Blackmore Collection)

This technique of hunting is still used by the pigmies of present-day Africa, although the Saxon site was certainly’ between 70,000 and 100,000 years old. Production rates of flint implements must have been considerable, for the numbers discovered have been very large indeed. A count made of one site revealed no less than 459 flint hand axes which had been left among the bones of a hippopotamus; presumably all had been blunted or broken during the hacking up and prolonged consumption of this massive beast, which must have represented many days’ food for a small tribal group. Although in Europe flint was to be ousted by copper, bronze and iron, in more remote parts of the world its use continues into the present day. Primitive men have always used flint alongside local sources of durable points and edges for their tools and weapons.

Travellers accounts tell of many strange devices; in Cambodia, for instance, the spike of the sword fish was used as a lance, and incredibly enough was used to attack and kill such animals as the rhinoceros. Horns of walrus and antelope were used for lance heads; the Red Indian, particularly the Iroquois, fitted some of their war clubs with a four-inch length of deer’s horn—although by the 1870s this was usually replaced by the far more efficient blade of a European knife.

Teeth from sharks and other creatures were used in Oceania in much the same fashion as the microliths of primitive man. Wooden formers were shaped and a ridge cut along the edges, and into these were glued (by means of resins) or tied by vegetable fibres a row of teeth with the point outwards— the whole making an extremely vicious and dangerous slashing weapon. A similar primitive form of sword was found by Conquistadores when they landed in South and Central America.

The Aztec war club or maquahuilt was fashioned in exactly the same manner using pieces of obsidian; this was a very suitable form of stone, volcanic in origin, glass-like in nature, and capable of providing an extremely sharp cutting edge. The small pieces of obsidian were secured into the sides of the weapon by vegetable adhesives or by thonging, and this technique evidently spread further north, for a number of Iroquois graves were found to contain small flints presumably used in exactly the same fashion.

Buy first bronze swords for collectibles

The aboriginies of Australia are today still fashioning stone arrow heads and spear heads, although now they often use glass, telegraph insulators, or any other man made materials upon which they can lay their hands. It may seem anachronistic that the use of flint has persisted so long; but for anybody who has tested the edge of a flint implement it will come as no surprise to learn that they are remarkably sharp and efficient.

It is not surprising therefore, that when Captain Cook first visited Tahiti he found it extremely difficult to convince the natives of the efficiency of metal. It was only when he had a metal adze fashioned in the same style as one of their stone adzes and compared their efficiency that they condescended to try it and began to appreciate the greatly increased cutting capability of the metal.

Techniques evolved by primitive man are surprisingly complex and modern research is still unable to reproduce some of the effects which ancient man regularly achieved. Much has been deduced from close examination of surviving flints and several feasible methods of working have been provisionally identified. Some of the later neolithic flints are of extraordinarily fine quality, polished, smoothed and shaped to precise and geometric patterns. However, there comes a point beyond which flint cannot be developed, for it is a brittle substance and if extended beyond a certain length it will soon shatter if struck. This means that the production of flint swords or even long bladed daggers was impossible.

Certainly flint knives of greater than usual length have been found in Denmark, but these were possibly either ritual objects or cutting implements for crops and would never have survived in battle. It is to the Middle East that man apparently owes the introduction of metallurgy into his technology. On a site excavated in modern Iran, near the village of Sialk, were found some small pins, or perhaps drills, of hammered copper. Radio carbon dating—a comparatively exact method of determining age—has suggested that these date from around 5,000

Buy antique bronze swords for gift

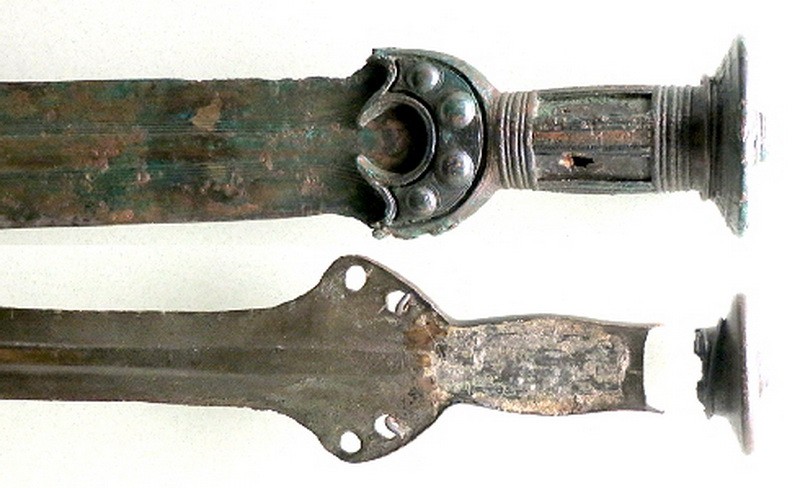

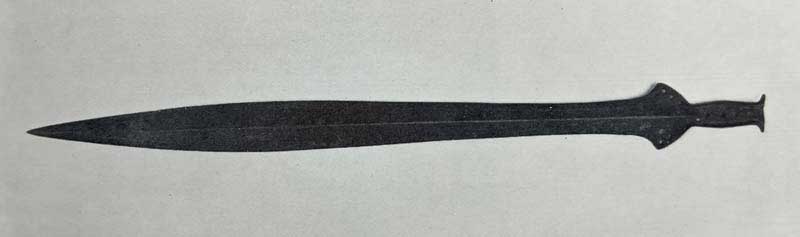

B.C. Copper is, of course, a very soft metal and no doubt Iranian man experimented with copper by producing moulded or hammered blades for daggers and smaller items; but it is unlikely that swords of any consequence were developed. The softness of the metal would not allow a weapon to retain an edge for any length of time. In fact, despite the freedom that copper gave to the smith to produce any shape he wanted, it was in many ways inferior to flint. Whether by accident or by design the metalsmiths discovered that the addition of a very small amount of tin to copper would produce a harder metal, and with this discovery dawned the Bronze Age. Analysis of early bronze items has established that most bronze contained only 10% of tin—although small amounts of a number of other compounds such as zinc, lead and silver were all used. Bronze was both cast and wrought; most of the axeheads were almost certainly cast by using two-piece moulds.